News & Updates

Obstetric fistula stories and announcements

Obstetric fistula stories and announcements

Mulanje, Malawi – Alice Sabuni has been living with obstetric fistula since 1949, when she gave birth to her first child, at age 17, a year after she was married. Now 83, many of her recollections from those days have grown a bit hazy, but she vividly remembers being in labour – and pain – for two days before she was taken to a hospital.

Read MoreMulanje, Malawi – Alice Sabuni has been living with obstetric fistula since 1949, when she gave birth to her first child, at age 17, a year after she was married. Now 83, many of her recollections from those days have grown a bit hazy, but she vividly remembers being in labour – and pain – for two days before she was taken to a hospital.

As a result of the excruciating ordeal, she developed fistula – a hole between the birth canal and bladder or rectum that is usually caused by prolonged or obstructed labour. The condition results in chronic incontinence, infections and, all too often, fierce discrimination.

“Obstetric fistula is almost exclusively a condition of the poorest, most-vulnerable and most marginalized women and girls,” says UNFPA Executive Director, Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin. “It afflicts those who lack access to the timely, high-quality and life-saving maternal health care that they so desperately need and deserve, and that is their basic human right.”

In November, after 66 years of shame, hiding and discomfort, Alice discovered that she might finally have the chance to end hers.

Holding out hope for a cure

Globally, two million women and girls suffer from the devastating condition, and although it is almost entirely preventable, between 50,000 and 100,000 still develop the injury annually. In most cases, it can be repaired with a simple surgery, but in many areas women lack awareness of or cannot afford the procedure, and doctors are not properly trained to perform it.

And so, due to the stigma – and isolating stench – that often accompanies the condition, fistula condemns many women to a lifetime of being shunned by their family and community, and it is not unusual to find them living alone in huts on the fringes of their villages and towns, isolated, unemployed and alone.

Despite living with her injury for the better part of a century, Alice says she is lucky. Unlike many women with fistula, her husband stayed with her for decades. And with help from him and her sisters, she was able to hide her injury from most of the people living in her small village, 60 kilometres from the city of Blantyre, and avoid widespread discrimination.

“I think this man loved me a lot because most men would not stay with a woman who had this condition,” she says. But even with her family’s help, some of the village residents did discover her condition. “There have been times when people thought she was bewitched,” says her niece, Shone.

However, Alice was always considered the strong one among her sisters, and even in the face of these pernicious, and possibly dangerous, rumours and the discomfort of her injury, she stayed determined. Over the years, she gave birth to five more children, supported her family by farming – despite her incontinence, and eventually welcomed 25 grandchildren into the world.

But still, even though her family had accepted her condition as permanent, she held out hope that with everything she had lived to see, she might live to see a cure.

Ending fistula one surgery at a time

In 2003, UNFPA launched the Campaign to End Fistula with partner organizations, and in 2007, the campaign came to Malawi, where at least 20,000 women are estimated to have obstetric fistula. As part of the campaign, UNFPA Malawi brings in foreign experts to train local clinicians on repair surgery, works to improve awareness of fistula and link women to care and holds rotating fistula camps around the country – during which women can access free fistula repair services.

In November, Shone heard on the radio that one such camp was coming to the Mulanje District Hospital, only a few hours away from their village, and though many members of the family were suspect that the treatment could work, she decided she had to get Alice there.

She succeeded. And Alice was among the 21 women who received surgery as part of the two-week camp.

“I am healed, save for a few emotional wounds that are taking time to heal. Where were you all these 66 years?,” she says. “I would not have suffered as much if I had received this treatment earlier. Regardless, I am a happy person now.”

The story was first published on UNFPA.org

Headlands, Zimbabwe – A year ago, Tuwede Adam (36) was sitting in her home dejected and sad having suffered from fistula for 19 years. In 1996, while giving birth at home during an agonizing 4 day labour at the age of 16, Adam suffered this birth injury that left her incontinent. Since this injury, she had lost her social life, ostracized by her community in Headlands in Zimbabwe’s Manicaland province.

Read MoreHeadlands, Zimbabwe – A year ago, Tuwede Adam (36) was sitting in her home dejected and sad having suffered from fistula for 19 years. In 1996, while giving birth at home during an agonizing 4 day labour at the age of 16, Adam suffered this birth injury that left her incontinent. Since this injury, she had lost her social life, ostracized by her community in Headlands in Zimbabwe’s Manicaland province.

“This illness troubled me a lot for so many years. I was ashamed because of my condition,” said Ms. Adam. “My life was about staying indoors…I could not go for community meetings where others were. I could not go to church, even to attend funerals. My life was just about staying indoors or at home on my own…I just could not go anywhere where people were.”

However, today Ms. Adam sits in her home a much happier person. She was one of 145 women who received life changing fistula reconstructive surgery since August 2015 thanks to support from UNFPA Zimbabwe and its partners, the Ministry of Health and Child Care and the Women and Health Alliance International (WAHA). Three fistula repair camps have been conducted so far at Chinhoyi Hospital, a government run provincial hospital in the Mashonaland West province of Zimbabwe.

Ms. Adam was one of first women to undergo this surgery, which she says has changed her life significantly. She is no longer a social outcast in her community. She can now attend social gatherings, travel and visit relatives living across the length and breadth of Zimbabwe and now even has her own market where she sells various wares such as tomatoes.

“After my treatment I sat down and started thinking about what I could do to sustain myself. It was then the season of ripening of mazhange (a wild fruit). So I went and I picked some in the forest and came to this road to sell,” said Ms. Adam. “From the proceeds of the sale, I then bought a gallon of tomatoes which I sold at the market and on the roadside. I have been doing this then. The last time I made profit, I managed to buy laundry soap and cooking oil for my family.”

Before the surgery, Ms. Adam and her husband had tried everything they thought would make her better.

“I had gone to hospital to seek help, I had gone to some church prophets and traditional healers to try and get help but everything failed,” says Ms. Adam.

‘You should not rush to traditional healers’

Ms. Adam’s husband, Roddrick said his wife’s treatment opened his eyes to the importance of seeking medical care. “It was a lesson for me that if you are ill you shouldn’t rush to n’angas (traditional healers) or church prophets because some conditions require medical attention,” he says. “I encourage other women with similar conditions to go to the hospital instead of just staying at home and thinking of getting help elsewhere. I encourage other men with wives suffering from this condition, to be supportive as possible in seeking medical treatment.”

Life changing stories such as that of Adam continue to push for reconstructing the lives of many women. With over 500 women currently on the camp’s waiting list for free repair surgery, UNFPA Country Representative Cheikh Tidiane Cisse said that UNFPA is committed to supporting Ministry of Health and Child Care to address the problem of fistula in Zimbabwe.

“It is these heart rending tales from women such as Adam that really give us the urge to want to continue reaching out to many other women,” said Cheikh Tidiane Cisse. “We will continue mobilizing for support for the Campaign to End Fistula so that we can restore the dignity of many other women who have fistula and prevent such birth injuries.”

Ms. Adams now looks to the future with renewed energy. She hopes to one day go into poultry or become a small scale subsistence farming, selling her produce at wholesale price in the capital city of Harare.

“I lost so much time over the years; I need to catch up,” she says with a smile.

- Bertha Shoko and Victoria Walshe

The story was originally published on UNFPA Zimbabwe’s website.

![]()

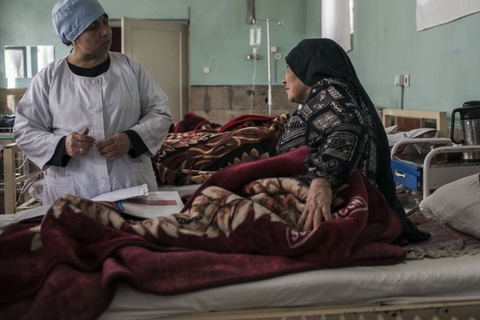

Kabul, Afghanistan - Within the gates of Malalai hospital hundreds of women, children and anxious men sit in the few sunny areas of the courtyard, bouncing sick babies on their laps, waiting. Inside the female-staffed maternity hospital, the halls resonate with the moans of women in labor while they share beds in crowded rooms humid with the stress of new birth.

Read MoreKabul, Afghanistan - Within the gates of Malalai hospital hundreds of women, children and anxious men sit in the few sunny areas of the courtyard, bouncing sick babies on their laps, waiting. Inside the female-staffed maternity hospital, the halls resonate with the moans of women in labor while they share beds in crowded rooms humid with the stress of new birth.

Further down a maze of hallways, hidden at the end, is a silent space where seven women sleep under heavy blankets. Exhausted and worn as if ending months of weary travel, these women are recovering from fistula surgery, and more importantly, from years of exclusion from society. Because of the constant smell of urine that caused them heartbreak and shame, they were shunned from everyday life, unseen in daily life, and abandoned by their husbands.

Obstetric fistula is a devastating injury acquired during prolonged or obstructed labor without timely access to emergency obstetric care, resulting in a hole between the vagina and bladder or rectum, which leaves women leaking urine or feces. The fistula ward in the Malalai Maternity Hospital, supported by UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund and Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health, is one of few places in Afghanistan women can receive free emergency obstetric care and surgeries by trained female surgeons.

Fistula surgery is the solution to a problem that often seems unapproachable in Afghanistan. In some ways, women with fistula issues are considered the lucky ones, surviving the high maternal mortality rate that haunts Afghanistan; though none of them would think of themselves as lucky. A lack of maternal care and education, malnutrition, child marriage, remote villages on rarely traveled roads, society’s powerless role for women, not to mention ever-raging war, all stack up against women who suffer this problem.

Noorjahan, 67, lived with fistula for 49 years until her recent surgery. During those years she hid in one room, rarely leaving, sewing to make a living. Every morning, afternoon and evening she cleaned her soaked mattress and searched for plastic bags that she tied around her like diapers.

To find the fistula ward, Noorjahan traveled from far away to reach Kabul, a difficult task for an illiterate woman with obstetric fistula, hanging on a rumor she had heard about the existence of doctors who could help her. For four days she wandered the streets of Kabul before finally finding Malalai Maternity Hospital and the fistula ward inside.

Now, days after surgery, Noorjahan smiles.

“I can die now. My grandchildren will play with me. I am clean. I can practice my faith. I can live,” she says with a laugh that ends only because of the pain leftover from surgery.

While she drinks tea, delicately rearranging herself in her bed, she is visited by former patients who now are attempting normal lives and have returned to the ward for a check-up. They interact like war veterans, understanding the torment of their lives without having to speak of it, checking in with each other in the recovery room, and sharing each other’s silent tears after nightmares about the life before.

One such fistula veteran is Guldesta. She married at the age of 12 and had a son at 13 in the distant region of Pul-e Khumri. She had two daughters, then several miscarriages that led to an obstetric fistula. She lived with the injury for many years until her surgery at Malalai Hospital.

“People have told me not to take my daughter or daughter in law to a hospital when she is about to give birth, but I have never listened to them. I have seen so many problems and difficulties of fistula. I wasn’t able to sit a minute with my guests because I had a bad condition. I was sitting alone for days and nights,” she said.

Now, she is a mother-in-law with a grandchild.

Guldesta’s is a rarity in her community. Living in a three-room home without running water that she shares with over 15 people, she lives in a community where poverty is rampant and education is scarce. But through her own experiences with fistula and the doctors who helped her, she has made it her duty to educate others, starting with her own family.

“My daughter is too young to marry now, but I will see what the future brings us. My older daughter is married to a man in Jabulsaraj (a district in Parwan) and there are not many hospitals around. She is here now and I will take her to Malalai Hospital whenever she is about to give birth.”

Doctors who work with UNFPA and the Ministry of Public Health say that lack of education is at the center of the problem. Compared to the amount of women who suffer from an obstetric fistula in Afghanistan, very few have actually made it to Malalai Hospital for care.

UNFPA attempts to address the issue by supporting training of female midwives and doctors who can help women with preventing and recovering from this injury as well as educating men and women on the problems of child marriage.

“Women wouldn’t be allowed to come to the hospital if there were male doctors,” says Dr. Nazifa Hamrah, 51, a fistula surgeon. “All of my colleagues are women, so we are very comfortable and can focus on our work.”

The training of midwives to work is central to preventing fistula. UNFPA supports training of midwives who are selected from their rural communities through a process involving families, shuras and elders to make it a community decision to educate women as midwives, showing its importance to all involved. The process also ensures that future midwives return to serve the community once they have completed their education in the Family Health Houses that the community have built.

In these regions finding girls who have completed a 10th grade education is often difficult. An 8th grade education is required. But, through training, these midwives have become the heroes to women in their region, one doctor said.

Sina Alizada, 41, trained as a midwife in the mountains of Bamiyan. House calls were made by horse, the roads too treacherous for cars or motorcycles.

There are many issues related to fistula problems in Afghanistan that need more attention, explained UNFPA Representative, Bannet Ndyanabangi. “The isolation and stigma of the recovering women is not over even after medical treatment. The survivors need help to start making a living and for reintegration into their communities for a life of dignity and hope.”

- Andrea Bruce

Dharan, Nepal – When Rita Devi Chaudhary gave birth to her first child, at age 23, a small fistula that had caused her mild discomfort since age 10 tore into a much larger injury. As a result, like many of the 2 million women living with the condition globally, she began to suffer chronic incontinence – and constant humiliation and discrimination.

Read MoreDharan, Nepal – When Rita Devi Chaudhary gave birth to her first child, at age 23, a small fistula that had caused her mild discomfort since age 10 tore into a much larger injury. As a result, like many of the 2 million women living with the condition globally, she began to suffer chronic incontinence – and constant humiliation and discrimination.

It was the year 2000, and though fistula – a tear or hole in the birth canal that often results in leaking of faeces and urine and dangerous infections – has long been preventable and treatable, at the time, awareness around the condition and access to the surgeries to repair it were extremely low in Nepal.

And Rita could find little information about the injury that had suddenly upended her life. “I was leaking bodily fluids for two years before I went to seek treatment,” she says.

Rita first visited the city closest to her home village in the foothills of the Himalayas. After failing to locate a physician trained to perform fistula repair surgery there, she used the little savings she had to travel the country.

However, in clinic after clinic, she couldn’t find a doctor trained to treat her. “Eventually, I decided to try to find help in India,” she says, but there too she could not access properly trained medical professionals.

“Doctors there tried to treat me for one month, but they couldn’t fix the problem. They referred me to another hospital, but the fee was very high, and we were very poor, so I came home,” she says.

Forced to live in isolation

Fistula is most commonly caused by prolonged or obstructed labour, and can be nearly eliminated by ensuring the presence of a skilled birth attendant during all deliveries. However, in Nepal, only 55 per cent of births are attended by skilled health workers, and this low rate not only leads to fistula, but also to a national maternal death ratio of 258 deaths per 100,000 births – one of the highest incidence in Asia.

In addition, as Rita discovered, until recently, few physicians were trained in obstetric fistula repair, and when these surgeries were available, they often cost more than the women most likely to need them could afford.

This left fistula sufferers, who frequently develop the condition when they are quite young, with few options other than a lifetime of dealing with fistula and the intense stigma, discrimination and abandonment by family and friends that often accompanies it.

Another twelve years passed after Rita’s journey, during which she gave birth to five more children – and with each delivery, her injury worsened. Soon, she was living in total isolation, and for years did not attend a single event outside her home.

“I was always leaking, and the smell was very embarrassing, and many would refuse to eat any food I made,” she says. “I kept wondering, ‘when will I be cured so I can wear nice clothes and join my community.’”

However, unbeknownst to her, the lack of treatment and awareness she had confronted when traveling Nepal had already begun to change.

Raising awareness proves key to improving treatment

In 2010, the Campaign to End Fistula launched in Nepal, and programs to prevent and treat fistula and reintegrate the previously isolated women who had received repair surgeries back into society began opening throughout the country.

Then in 2014, a skilled birth attendant, who had recently started working in Rita’s community, referred Rita to a hospital supported by UNFPA, the United Nations Populations Fund, in the nearby city of Dharan, telling her should could now receive the treatment she had searched for for so long – free of charge. “Finally, I feel as though I am cured,” she says.

However, in April 2015, a devastating earthquake destroyed 84 per cent of the Nepal's health facilities, interrupting efforts to improve fistula treatment. But clinics and hospitals are now reopening.

And in November, the government officially launched and began to broadly disseminate a competency-based training manual on how to manage, treat and prevent obstetric fistula. The manual had first been developed, approved and employed to effectively train a limited number of surgeons and nurses in 2014, before the quake hit, with support from UNFPA and Jhpiego.

“Because of the Campaign to End Fistula, the government has improved its policy, and fistula checks are now a regular part of post-natal examinations,” says Dr. Mohan Chandra Regmi, the fistula surgeon at BPKIHS, the hospital in Dharan where Rita received her surgery. “The main challenge now is client identification, awareness and reintegration. Because of their social isolation, [fistula sufferers] don’t come out of their homes, much less visit a health centre. We need to find new cases early on to prevent this isolation."

The story was originally published on UNFPA website.

Batouri, Cameroon – Due to complications during the birth of her 11th child, Zandelé Colette, now 56, underwent an emergency caesarean section. However, the procedure occurred too late to save the child, who died shortly after birth, and, as a result of the prolonged labor, Zandelé developed fistula.

Read MoreBatouri, Cameroon – Due to complications during the birth of her 11th child, Zandelé Colette, now 56, underwent an emergency caesarean section. However, the procedure occurred too late to save the child, who died shortly after birth, and, as a result of the prolonged labor, Zandelé developed fistula.

Fistula is a hole in the birth canal that results in chronic leaking of faeces and urine and causes women who experience it to face frequent infections. In addition, due to stigma against the condition, the women are often abandoned by their husband and family, denied employment and left facing deepening poverty in total isolation. For over 20 years, Zandelé suffered these devastations. “My life has been made rotten by fistula,” she says, adding that, after all that time, she had lost hope for a better future.

Then recently, with the help of Marie, Alice and Rachel – community health workers from the UNFPA-supported Women's Centre for Information, Listening, and Psychosocial and Legal Assistance in Batouri, a town in eastern Cameroon – her life finally changed.

Searching for women in need

As part of their role at the Listening Centre, Marie, Alice and Rachel search the communities and villages surrounding Batouri to find women suffering from fistula, often venturing into remote areas where the women exiled due to fistula can be found living alone in deplorable conditions. “I love what I do, because I know that these actions are improving many lives,” says Marie. “I wish I had a motorbike, then I could reach five times as many women.”

Rachel found Zandelé, who was living in such isolation in the small town of Ndelele, and brought her to the Listening Centre, where she received counselling and support. Then, after scheduling an appointment for Zandelé's treatment, Alice led her to Ngaoundéré Hospital fistula repair centre.

Despite the fact that obstetric fistula is almost entirely preventable through proper maternity care and, if it does occur, can be repaired through a simple surgery, many of the world’s most vulnerable women cannot access this treatment and care.

Globally, more than two million women are estimated to be living with fistula, and between 50,000 and 100,000 new cases develop each year. In Cameroon, which has one of the world’s highest rates of maternal mortality, an estimated 20,000 women are currently living with fistula, according to the 2011 Demographic and Health Survey.

“Now, I am happy because I have been to the Ngaoundéré Hospital fistula repair centre,” says Zandelé. “I no longer feel the urine running down my feet as before. And I am very grateful to all the people who helped me to get cured of this shameful disease.”

Providing hope and services

The centre at Ngaoundéré Hospital, which opened with UNFPA support in 2014, is the first permanent fistula repair facility in Cameroon. Prior to its establishment, most women in need of fistula repair could not pay for the surgery. “Fistula victims were generally frustrated when they came to the hospital, because they were asked for a lot of money before they could receive any intervention, but most of them are very poor,” says Dr. Danki Sillong, director of the repair centre. “With UNFPA’s support, this is no longer a problem.”

In addition to supporting the centre, UNFPA is distributing free fistula repair kits, which contain all the supplies and equipment necessary to repair fistula, across Cameroon. It is also working with the Ministry of Women's Rights, Child Protection, Family Welfare and Consumer Protection to train health workers and develop a printed guide about how to care for women with fistula.

Messanga, age 20, had been living with fistula for four years when the Listening Centre outreach workers brought her to Ngaoundéré Hospital. “I would like to say thank you very much to the whole chain that was set up,” she says. “I considered myself as dead, and [the surgery] has allowed me to live again.”

– Olive Bonga

First published on UNFPA.org

N’DJAMENA, Chad – Like many child brides, Micheline Yotoudjim suffered terribly after she was married. She was married off at age 14, became pregnant at 16, and then experienced a prolonged, obstructed labour. Her baby was eventually delivered through a Caesarean section, but died four days later.

Read MoreN’DJAMENA, Chad – Like many child brides, Micheline Yotoudjim suffered terribly after she was married. She was married off at age 14, became pregnant at 16, and then experienced a prolonged, obstructed labour. Her baby was eventually delivered through a Caesarean section, but died four days later.

The complications caused Ms. Yotoudjim to develop an obstetric fistula – a hole in the birth canal that causes chronic incontinence. It can also lead to a host of other problems, including infections and infertility.

Women are too often blamed for the effects of fistula, and many are ostracized by their families or communities. Ms. Yotoudjim was no exception; husband abandoned her.

It took four years and five surgeries to repair the fistula.

“I still have nightmares when I remember how I used to smell back then,” she said.

Obstetric fistula is a needless tragedy, easily remedied with access to emergency obstetric care. Yet it happens all too often in Chad, experts there said, not only because women lack access to proper maternal health care, but also because traditional practices put girls at increased risk – namely, child marriage and adolescent pregnancy, which expose girls to physical risks before their bodies are mature.

“It is a cultural problem, and it is not easy to change behaviours,” said Dr. Koyalta Mahamat, director of the National Centre for the Treatment of Fistula, the country’s leading fistula treatment facility, in N’Djamena, the capital.

Child marriage and adolescent pregnancy are common in Chad. The median age of marriage for women is about 16, according to the country’s 2004 demographic and health survey, the most recent such survey available. Chad’s adolescent birth rate is 203 per 1,000 girls, according to the 2015 State of World Population report. By comparison, the global adolescent birth rate is 51 per 1,000 girls.

Messages about the harms of these practices, and about importance of proper maternal health care, are being disseminated through radio, television and other media. Still, there are still numerous barriers to change.

But people like Ms. Yotoudjim are making a difference.

After Ms. Yotoudjim recovered from the fistula, her husband said he wanted to reconcile.

She refused.

Instead, she dedicated herself to helping other women with the same condition.

Fourteen years later, she is a passionate advocate for survivors of fistula. She is also a nursing assistant, helping Dr. Mahamat and other health workers in the operating theatre where women are treated.

“I also counsel and give them support to help them go through the experience,” she said.

UNFPA supports the treatment centre with hospital equipment and reproductive health supplies, and helps with the cost of each surgery. UNFPA also supports the training of midwives and other health workers, part of broader efforts to improve maternal health.

About 2,000 women received surgery between the centre’s opening in 2007 and the end of 2014, Dr. Mahamat said.

But recovery does not end with a successful operation. Having suffered years of stigma and isolation, fistula survivors often have difficulty returning to their communities. Many have been excluded from work or school, and as a result have endured crushing poverty.

The Association for the Reintegration of Victims of Fistula, known by its French acronym ARF-VF, provides training in skills that help survivors earn an income, easing their return home.

Located near the fistula treatment centre, ARF-VF teaches weaving and tailoring skills, and provides information about running a sewing business.

“We give equipment such as sewing machines and provide advice to enable them start life again,” said ARF-VF’s founder, Benjamin Toldibaye, a Catholic priest.

The organization receives assistance from UNFPA, the African Union, the US embassy, and the country’s first lady. Some of the women’s products are sold through a nearby Italian non-governmental organization, Mr. Toldibaye said.

– Paul Okolo

United Nations, New York – The United Nations General Assembly adopted a UNFPA-backed resolution on obstetric fistula on 18 December 2014, which calls for stepped-up actions to end the condition.

Learn moreUnited Nations, New York – The United Nations General Assembly adopted a UNFPA-backed resolution on obstetric fistula on 18 December 2014, which calls for stepped-up actions to end the condition.

“The resolution is important for millions of women suffering the pain and shame of fistula,” said Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, Executive Director of UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund. “With the backing of the international community, UNFPA and its partners in the Campaign to End Fistula can continue to step up our efforts to prevent fistula and treat and re-integrate fistula survivors.”

The UNFPA-led Campaign to End Fistula currently supports about half of all fistulas surgical repairs in developing and emerging countries, where the condition is more prevalent. The number of fistula repairs supported by UNFPA doubled from 5,000 in 2010 to more than 10,000 in 2013. Since 2003, the Campaign has supported more than 47,000 fistula repairs.

The new resolution calls on the international community to intensify technical and financial support to accelerate progress in the remaining days until the deadline to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5 (to improve maternal health) by the end of 2015 and eliminate fistula.

Co-sponsored by more than 150 Member States and adopted by consensus, the resolution also acknowledges obstetric fistula as a notifiable condition, and, as a result, fistula survivors should be registered and tracked in order to receive necessary medical treatment and follow-up medical care for future pregnancies.

Fistula is a childbirth injury caused by prolonged, obstructed labour. It is estimated that at least two million women live with the condition. There are 50,000 to 100,000 new cases per year. Working with more than 90 partners in more than 50 countries, the Campaign to End Fistula strives to make obstetric fistula as rare in developing and emerging countries as it is in industrialized nations.

The General Assembly enshrined the text adopted by its Committee on Committee on Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Issues in November. Read more about the resolution.

The reportage from Afghanistan, Nepal and Pakistan highlights the efforts in treating fistula through stories of women who endured and overcame the condition.

Watch the videoThe reportage from Afghanistan, Nepal and Pakistan highlights the efforts in treating fistula through stories of women who endured and overcame the condition.

In Bangladesh and across the developing world, UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund supports efforts to repair obstetric fistula, a serious and tragic complication related to childbirth.

Watch the videoIn Bangladesh and across the developing world, UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund supports efforts to repair obstetric fistula, a serious and tragic complication related to childbirth.

DHAKA, Bangladesh – For women suffering from obstetric fistula, a traumatic and debilitating childbirth injury, the effects are much more than physical. The condition often leaves them stigmatized by their communities, abandoned by their families and unable to work. And treatment alone does not end this ordeal. After years of isolation, they have to learn to rebuild their lives.

A rehabilitation centre in Bangladesh is helping fistula survivors do just that.

Read MoreDHAKA, Bangladesh – For women suffering from obstetric fistula, a traumatic and debilitating childbirth injury, the effects are much more than physical. The condition often leaves them stigmatized by their communities, abandoned by their families and unable to work. And treatment alone does not end this ordeal. After years of isolation, they have to learn to rebuild their lives.

A rehabilitation centre in Bangladesh is helping fistula survivors do just that.

Nasima Nizamuddin, who struggled after being rejected by her husband, says the fistula centre helped her heal, and it is giving her the skills to support herself.

Now, she says, “I don’t feel alone anymore.” See more